In this episode of The Voices of History, we meet Dr Mohamed Keshavjee, a former governor of The Institute of Ismaili Studies in London. A specialist in Alternative Dispute Resolution, Dr Keshavjee was responsible for training mediators for the Conciliation and Arbitration Board, where he conducted training programmes in some 25 countries in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

Rizwan Karim, coordinator for the Oral History Project, sat down with Dr Keshavjee for an exclusive interview.

Watch the episode below or listen on Spotify.

As a young boy in the midst of global decolonisation, Dr Keshavjee witnessed first-hand the political and social upheavals that shaped South Africa’s freedom movement. He reflects here on a time of struggle, hope, and transformation.

“It was a time of great excitement because apartheid was a very difficult situation. But I think it produced a lot of people, you know, artists, doctors, lawyers, economists, political scientists, social activists, political activists who were involved in the process of fighting for freedom.

“I remember our home as a place where a lot of discussions took place. My different siblings’ friends used to walk in and out. The Pretoria intelligentsia, many people who had been to university – Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg, used to find a ready welcome at our home. So, our home had people who were black, brown, white, and people walked in and there was always a discourse. And I think that 1960 was an important time because that’s the time when the Sharpeville massacre] changed the destiny of South Africa because the political movements now were not able to operate within the country but had to leave for other parts of the world from which the freedom movement gained acceleration. So people like Nelson Mandela, Walter Sizulu, Oliver Tambo”

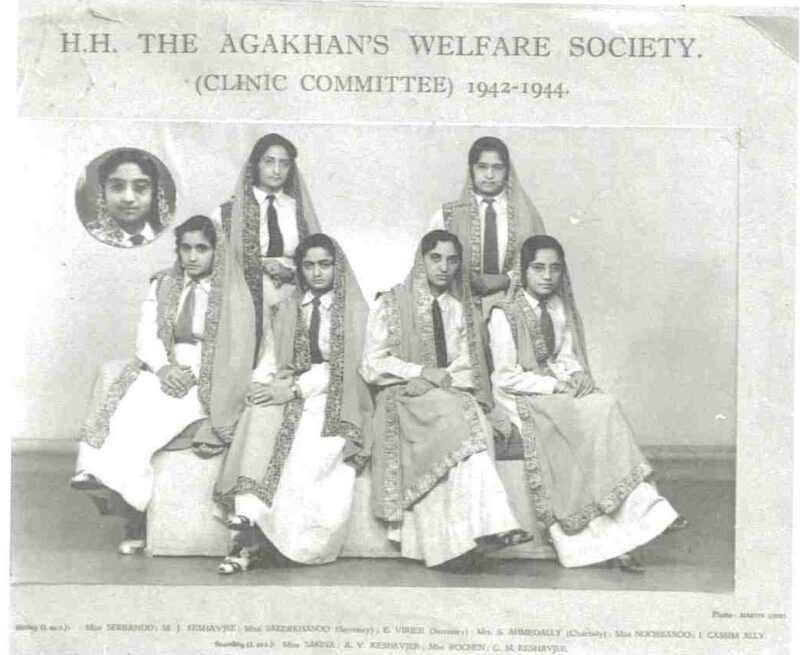

Here Dr Mohamed Keshavjee reflects on how his father Nazaraly Manjee Keshavjee navigated personal and professional challenges – not with resentment, but with a commitment to something greater than himself: “my father was responsible with his brothers for educating the first female doctor in the Ismaili community, a doctor called Dr Dolly Keshavjee (pictured on the right)… That means he didn’t let the conflict destroy this girl’s educational future. So, I thought that was to me a very deeply influencing moment as I became a lawyer, and I got into dispute resolution.”

Ismaili Women

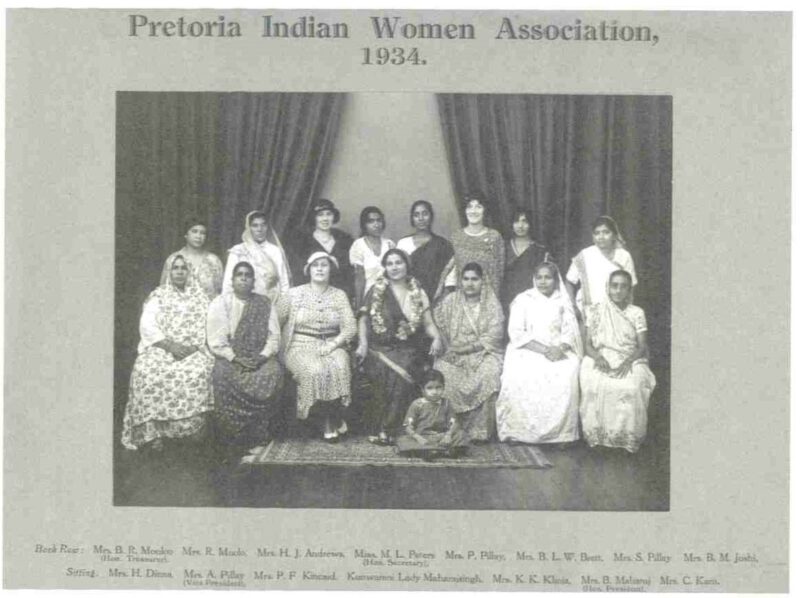

While history often amplifies the voices of men, women have been the quiet architects of community evolution. This is especially true in the Ismaili community, where women played a pivotal role in education, healthcare, and institutional development – often behind the scenes. Dr Mohamed Keshavjee’s mother, Kulsoom Manjee Keshavjee, was no exception. Coming from a distinguished lineage of religious education teachers, she and her sister became the first women appointed in 1946 to the Pretoria Provincial Council by His Highness Sultan Sir Muhammad Shah Aga KhanA title granted by the Shah of Persia to the then Ismaili Imam in 1818 and inherited by each of his successors to the Imamate. III, the 48th Ismaili Imam, a fluent English speaker and a strong advocate for education. She ensured that her children were deeply rooted in both secular and religious learning. Dr Keshavjee reflects on his mother’s influence – how she, alongside other pioneering women, shaped the intellectual and spiritual life of their community.

“Women were the institutional backbone,” Dr Keshavjee notes, “the whole Bait ul-Ilm (religious education) structure, the whole clinic that was started in Pretoria, the whole organisational ethos was largely pioneered by women.” Both his mother and his aunt, who were educated in Christian schools, played prominent roles in the Pretoria Provincial Council.

So, my mother played an important role, but I don’t think she was alone. She was part of a larger group of women… So, I think that influence is very much part of our home, and we grew up in it, and we lived that life.”

Reflections on the Aga Khan IV

Now, with the transition of the Ismaili Imamat from His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IVThe 49th imam of the Nizari Ismailis, Shah Karim al-Husayni, who succeeded his grandfather, Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III, in 1957. He led the Ismaili community for 67… More to His Highness Prince Rahim al-Hussaini Aga Khan VThe 50th imam of the Nizari Ismailis, His Highness Prince Rahim al-Husayni, who succeeded his father, His Late Highness Prince Karim al-Hussaini Aga Khan IV on 4th February 2025. More, his legacy continues to inform not only Dr Keshavjee’s own work but the broader Ismaili community and the world at large. Dr Keshavjee reflects on the legacy of His Late Highness, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, the 49th Ismaili Imam.

“Given this present moment, which is a moment of reflection for all of us in the JamatAssembly or religious congregation; also a term used by the Nizari Ismailis for their individual communities., in trying to reflect on the legacy of Mawlana Shah Karim Aga Khan IV, we are beginning to see how he impacted certain parts of our life, our reflections, our thoughts. And I thought I would touch on the things that I was fortunate to learn having worked under him for 30 years in three major areas of development, and I recall the first time I had formally met the Imam in an interview where he mentioned to me that

It is important that we speak about who we are and what we do after we have delivered what we said we would do… He said that when you talk about something, when you haven’t yet performed, then you do not have credibility. Whereas, if you do that and your work speaks for itself, then you don’t need much to say what you are doing.”

“Then there were other learnings that I gleaned, not through what the Imam said, but the way he did things,” Dr Keshavjee continues. “I came to realise that here was a very large vision, but it was underpinned by small steps… But one thing I learnt was that the Imam said: ‘go on a certain pathway of development, but don’t be rigidly fixated. If you feel you learn something, look at the little detour of how that could be valuable. And if you see that something is not viable, don’t be stuck. Be ready to change course but within a larger framework underpinned by thought, underpinned by ethical commitment, and underpinned by the bigger picture that the Imamat was committed to.” This viewpoint of His Late Highness, which Dr Keshavjee describes as a ‘multi-generational vision’ has guided both the work of Imamat institutions and of Dr Keshavjee.

Dr Keshavjee also shared an anecdote of personal care from the Imam, where he made time to meet a little girl between institutional meetings in Bangladesh: “he didn’t just walk out of the meeting and tell me, ‘Oh you sent me a note, but I was busy.’ No, he came out and said, ‘I wanted that.’”

Looking to the future

From a childhood shaped by apartheid to a life dedicated to the service of the Imamat, Dr Keshavjee’s journey reflects the resilience, adaptability, and vision of the Ismaili community of South Africa. Through the guidance of His Highness Aga Khan IV, this once-localised community expanded across the world, contributing to the work of Imamat institutions in meaningful ways. Dr Keshavjee shares how his own path — from law to mediation, from education to institutional development — highlights how the Imam has nurtured individuals to think beyond traditional frameworks. It is not just about professional success but about applying knowledge with purpose whether in justice, policy or community development.

“I went [to law school] when the decolonisation process was taking place in the world, a very critical time… But I think that in my own journey by the Imam, picking me out of the legal profession and placing me in three very important segments of the work that he wanted to see emerge in the years ahead. One was the field of information where I cut my teeth. on the first aspect or first part of my work in the Imamat, they were all overlapping. The second was in the restructuring of the Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Boards, where I was the coordinator globally for all the boards. For me it represented a very fascinating and very steep learning curve. And then, of course, the third part of my stay was in the field of Alternative Dispute Resolution, where Imam Karim Shah was very gracious in allowing me to go and do a Master’s and then a doctorate. But in the process, I realised that law was not a linear mechanical process, that law could be a great instrument for the upholding of justice. But equally I realised that law could also be an instrument of injustice depending how law is used in human society.”

Dr Keshavjee (pictured above) also shares stories from his life in South Africa in his book, Into that Heaven of Freedom: The Impact of Apartheid on an Indian Family’s Diasporic History.

Looking back, this is a story not of loss but of transformation — of a community that, despite displacement, found strength in continuity and hope. Today, IsmailisAdherents of a branch of Shi’i Islam that considers Ismail, the eldest son of the Shi’i Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), as his successor. from South Africa play critical roles in shaping civil society, academia, and global initiatives, carrying forward the ethics of their faith. Through life story oral histories, we capture not just memories but the spirit of service, dignity, and the enduring legacy of the Ismaili Imamat’s vision.

The Oral History Project

The Oral History Project of the Ismaili Special Collections Unit at The Institute of Ismaili Studies seeks to preserve the memories, experiences, and stories of members of the Ismaili communities across the world in their own voices.

Do you have a story to share with the IIS Oral History Project? If you want to share your memories, the story of your family, or the story of an elder you know, please reach out to the Oral History Project Coordinator, Rizwan Karim at rkarim@iis.ac.uk.

The Oral History Project