An Interview with Dr. Shafique Virani

Dr. Shafique Virani receiving the prestigious teaching award from The Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA) in 2010.

Dr. Shafique Virani, currently a Visiting Research Fellow with the IIS discusses the focus of his research at the IIS and scholarship on Islam more broadly for the IIS Update.

Please can you elaborate on the research project you are carrying out at the IIS and what you hope will be the outcome of this scholarship?

On the occasion of the Golden Jubilee of His Highness the Aga Khan, the IIS and the ISMC hosted him at a special ceremony in which he was presented with a number of new books. In his remarks on the occasion, His Highness singled out one particular dimension of the work of the IIS and ISMC that he described as “enormously exciting” - the identification and mobilisation of new source materials.

I’m very fortunate that my own research focusses on this “enormously exciting” area. When I wrote my first book, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages: a History of Survival, a Search for Salvation, perhaps the most thrilling part was discovering new sources of information in Arabic, Persian, Khojki, Gujarati, Sindhi, Punjabi, Siraiki, Hindi, Urdu and other languages, much of which had been unknown before. The new projects that I am currently working on are very much focused, once again, on the mobilisation of little-studied source materials.

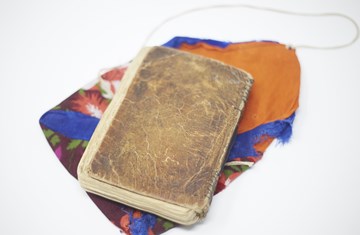

In Arabic, I’ve been working on the Asas al-Taʾwil of al-Qadi al-Nuʿman (d. 363/974), which explains the spiritual dimension and esoteric symbolism of the life stories of the prophets. This work was considered so important that it was translated into Persian as Bunyad-i Taʾwil, most likely by the illustrious Ismaili scholar al-Muʿayyad fi’d-Din al-Shirazi (d. 470/1078), and I hope to be able to publish this Persian version of the text as well. One of the most important historical sources for the Ismailis during the reign of the Safawid dynasty is the Risala of Khayrkhwah Harati (fl. 10th/16th c.). I have identified a number of new manuscripts for this work and hope to complete an updated critical edition and translation. Similarly, I’ve been studying the Tazyin al-Majalis or “Ornament of Assemblies” of the daʿi Husayn b. Yaʿqub Shah (fl. 11th/17th c.), which explains the spiritual meaning of a variety of festivals from the Muslim world, including ʿId al-Fitr, ʿId al-Adha, and Nawruz. One of the least studied areas of Ismaili history and thought is the Satpanth tradition of South Asia. To this end, I’m working on the Gujarati diaries of Pir Sabzali Ramzanali (d. 1938). Excerpts from all of these four projects were published in An Anthology of Ismaili Literature: A Shiʿi Vision of Islam in 2008.

In addition to the above four texts, I have also been working on several other items, including a text from Alamut known as the Tale of the Governor of Sistan (Qissa-yi Malik-i Sistan); a rare Syrian work from Alamut entitled The Protocols and Invitation of the Faithful to the August Presence (al-Dustur wa Daʿwat al-Muʾminin li’l-Hudur), which explains the process and meaning behind the oath of allegiance (bayʿa) that the believers pledge to the Imam of the time; Guidance for the Seekers (Irshad al-Talibin), which is one of the most important works available to us about the family of the Imam Shams al-Din Muhammad (d. ca. 710/1310); The True Dawn (Subh-i Sadiq) of Qasim Khurasani, who lived at the time of the Imam Dhu’l-Faqar ʿAli (d. 1043/1634) and The Spiritual Meaning of the Seven Pillars of the Shariʿah (Taʾwil-i Haft Arkan-i Shariʿat).

You have affiliations with many prestigious organisations, and a long relationship with the IIS. Can you tell us what prompted you to return to the IIS for these projects?

At my home institution, the University of Toronto, I’ve had the good fortune of contributing to scholarship in a number of senior administrative roles, including as Chair of the Department of Historical Studies, and as founding Director of the Centre for South Asian Civilizations. While involvement in these capacities has been very enriching, it leaves limited time for research activities. My sabbatical year provided an opportunity to return to the projects that I’ve described, and there was no better place to work on them than at The Institute of Ismaili Studies. The library collection here is unparalleled anywhere else in the world as far as holdings on Ismaili Studies are concerned. Being here also provides an opportunity to liaise and interact with outstanding colleagues who are involved with similar projects, to share ideas, and to work together on research of mutual interest.

How do you think scholarship and research can have a wider social impact?

There is a critical shortage of scholars of Islam in the West. While Muslims make up close to a quarter of the world’s population and Islam often dominates news headlines, academic expertise of this global faith is severely lacking. Just over ten percent of religion and theology departments at North American colleges and universities, for example, can claim to have faculty trained in Islamic studies, and statistics in the UK and the rest of Europe are probably similar. In his only known work, On Nature, the Greek philosopher Parmenides postulated that nature abhors a vacuum. The same might be said of a public in search of information. Where academics have not been able to satisfy the public’s thirst for knowledge, a host of dubious pundits have often been quite eager to pick up the slack.

Even leaving aside the insufficient number of academics in this field, the staid opinions of scholars are often at a distinct disadvantage in the public sphere, particularly in the free-for-all known as the Internet. In The Cult of the Amateur, Andrew Keen writes, “Out of this anarchy, it suddenly became clear that what was governing the infinite monkeys now inputting away on the Internet was the law of digital Darwinism, the survival of the loudest and most opinionated.” While this assessment is exaggerated, it is not entirely off the mark. Reliable, staid, and sober comment of scholars is often lost in a sea of uninformed, hateful and frequently hysterical supposition, trotted out by self- or media-styled “experts.”

As the proper functioning of civil society is premised on the existence of a well-informed populace, many members of the academy have tried to address this situation and to educate the general public about Islam through their writings, public lectures, media appearances and forays into the world of cyberspace, realising that they have responsibilities that extend far beyond the Ivory Tower. It was to address this problem that I edited a number of papers on the topic, “Speaking Truth beyond the Tower: Academics of Islam Engaging in the Public Sphere” for a special section of the Review of Middle East Studies. The authors of these reflections hoped that the methods contained in their papers may prove useful and replicable by others to ensure that sound scholarly information in our fields has the widest possible social impact and reaches the broadest possible public, often by ensuring that scholarly research is made more widely accessible online. Daniel Varisco expresses this very well in his contribution. He recalls the Quranic tale of the famous Yemeni dam of ancient Saba (Sheba). This was said to have been destroyed by a divinely sent flood on the unbelievers of the time. However, some commentators have opined that the real damage was caused by a little mouse, gnawing away at the base. Varisco asks playfully, “How much of the Islamophobia prevalent in the media and popular culture could be destroyed by scholars today with a simple click of a different kind of mouse?”