On a crisp autumn afternoon in October 2023, I sat with Dr Dil-Angaiz, an educationist and an assistant professor at Karakoram International University in Gilgit, inside the Faculty of Education building – an immersive, USAID-funded space dedicated to shaping future educators in the mountainous Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan. Outside, a student rally passed by, voices raised in protest against rising tuition fees. Inside, Dr Angaiz was quietly reflecting on her own educational journey as part of her interview for the Oral History Project (OHP) undertaken by The Institute of Ismaili Studies (IIS). The contrast was striking for me, an alumnus of the Graduate Programme in Islamic Studies and Humanities (GPISH) programme at IIS in London, as I interviewed a female scholar and educator from the region. Within a single generation, the meaning, access, and politics of education had undergone a profound transformation, with each era marked by its own struggles, sacrifices, and possibilities.

Dr Angaiz is among the pioneering women educators of Gilgit-Baltistan, whose life story is inextricably linked to the systemic changes that have unfolded in the region over the past five decades, particularly following the first visit of the 49th Ismaili Imam, His late Highness Shah Karim al-Hussaini, Aga Khan IV. Her journey, intertwined with that of her mother, Gul Fatima (whom I also interviewed for the project), offers a powerful lens through which to understand education not merely as personal advancement, but as a collective, faith-inspired project of social transformation.

A Daughter’s Departure, a Mother’s Resolve

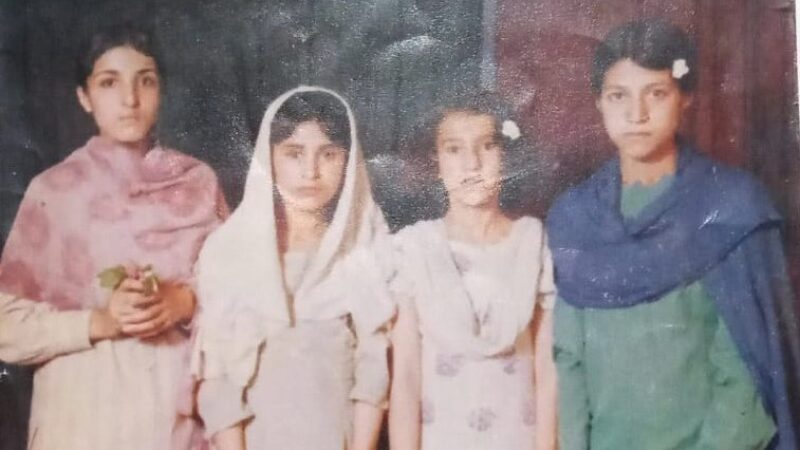

While tracing individuals who played catalytic roles in the region’s transformation after the 1960s, I came across a remarkable account: a small group of girls, chosen from remote mountain valleys, including Punial in the then Northern Areas (now Gilgit-Baltistan) of Pakistan, were sent to Karachi for education and health training. Among them was Dr Angaiz, just eleven years old, living a carefree life in her village of Sher Qila, unaware that a decision made by Ismaili institutional leadership would alter not only her future but also the educational landscape of her region.

This initiative, led by the Aga KhanA title granted by the Shah of Persia to the then Ismaili Imam in 1818 and inherited by each of his successors to the Imamate. Health Board, aimed to train local female health workers at a time when secondary and tertiary education was virtually inaccessible in the then-Northern Areas of Pakistan (now Gilgit-Baltistan). For Dr Angaiz, the decision was accepted without fear or hesitation, an instinctive trust that would later reveal itself as a defining force behind the region’s rapid social change.

She recalls that moment with clarity:

At that time, we had no understanding regarding how far Karachi is and whether a single female can travel all the way. … Since my father was a teacher himself, he agreed to it and told me [to go]. I was 11 years old at that point, and I was clueless and happy. But it was an opportunity that changed my life!

Yet while this journey marked liberation and opportunity for a young girl, it demanded an extraordinary sacrifice from those left behind, especially her mother. Gul Fatima’s recollection captures the emotional cost of this decision:

I was at home, our old house was over there. She came running and told me she agreed to go to the South (Karachi). I said, why do you want to go? We don’t have any relatives there! But she insisted, and I conceded. Right then, her father arrived and said if Hazar Imam asked us for something, even to jump in the river, we should do so! … As soon as the vehicle left, I fainted.

Even decades later, Gul Fatima remembers that day vividly, the tears, the farewells, the quiet grief of letting go. The sacrifice was not a single act, but a sustained commitment. Like many mothers of her generation in Ghizer, she continued to support the education of all her children, often through sheer resilience rather than material means.

She recalls being interviewed later in life:

They were curious to know how I endured it and how I supported my children, if I had resources to support my children? And I told them, no, what I had were tomatoes: I cultivated and sold tomatoes to support my eldest daughter’s education. Rest, we prayed for her. Her parent’s prayers, relatives’ prayers all yielded the outcome.

The Long Road of Learning

Although Dr Angaiz and her peers were initially expected to train as nurses and midwives, her path diverged. With the support of her hostel warden and mentor, Nazneen Rahim, she enrolled at an educational institute in Hyderabad. Communication with home was limited; her mentor wrote to her father to explain the decision and reassure him of her whereabouts. Each step forward involved uncertainty, courage, and reliance on a widening circle of mentors and institutional support.

Reflecting on this period, she recalls another pivotal intervention:

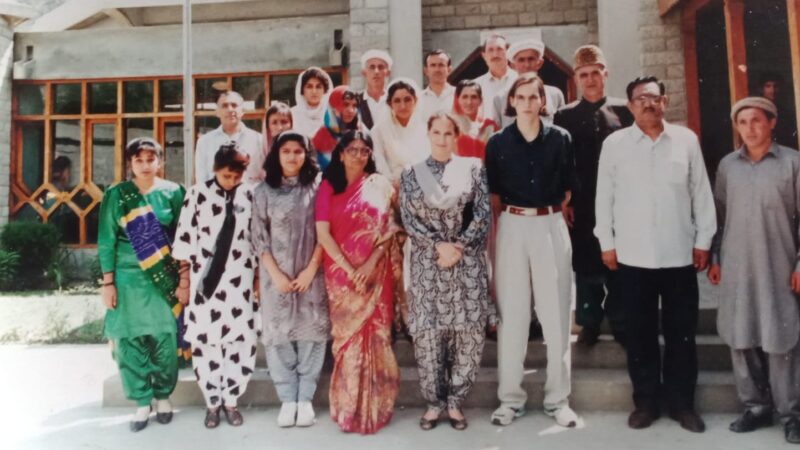

Sir Abdus Salam decided to open a hostel for girls after witnessing the kind of challenges I faced at the time. It’s the Al-Zahra Hostel located in Hyderabad, and he told me about the feasibility report. He mentioned how Ismaili girls coming from far-flung areas like North or rural Sindh face challenges, so there should be a hostel in Ismaili colonies for girls. … It opened and Hazar Imam [His Late Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan] inaugurated this hostel. And I was present there.

That day remains etched in her memory, not only because she saw the Imam four times in a single day, but because of the instruction he gave the students, she recalls hearing six times: to work hard. It became a guiding principle in her life.

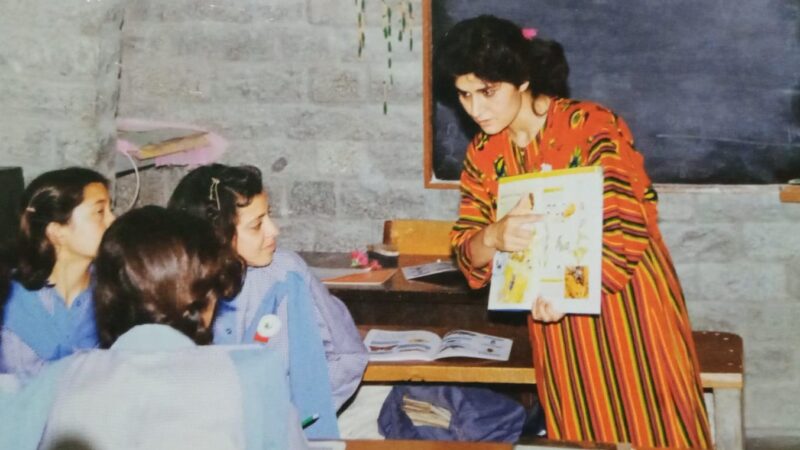

After completing her BSc, Dr Angaiz returned home and joined Aga Khan School Sher Qila, her alma mater. Her decision reflects how, for IsmailisAdherents of a branch of Shi’i Islam that considers Ismail, the eldest son of the Shi’i Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765), as his successor. in general and particularly in this region, spirituality and worldly progress are deeply intertwined:

In that dream, someone was introducing me to Hazar Imam [His Late Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan], and he patted my shoulder saying that she would be good for Aga Khan School Sher Qila and that thing in my dream became the ultimate dream of my life. I was stern that if mawla said it then I must go to Aga Khan School Sher Qila, regardless of what happened.

At the time, government educational infrastructure in the region was minimal. A generation earlier, one or two male teachers taught all subjects, with curricula limited to the Holy Qur’anMuslims believe that the Holy Qur’an contains divine revelations to the Prophet Muhammed received in Mecca and Medina over a period of 23 years in the early 7th century CE. More, Urdu, and basic mathematics. Building on the foundations laid in the 1940s of Diamond Jubilee Schools by the 48th Imam, His Highness Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan III, the establishment of Aga Khan Education Services (AKES) schools under His Highness Shah Karim al-Hussaini marked a turning point, not merely through the construction of buildings, but also through teacher training, curricular reform, and the production of locally trained female educators at the forefront of change.

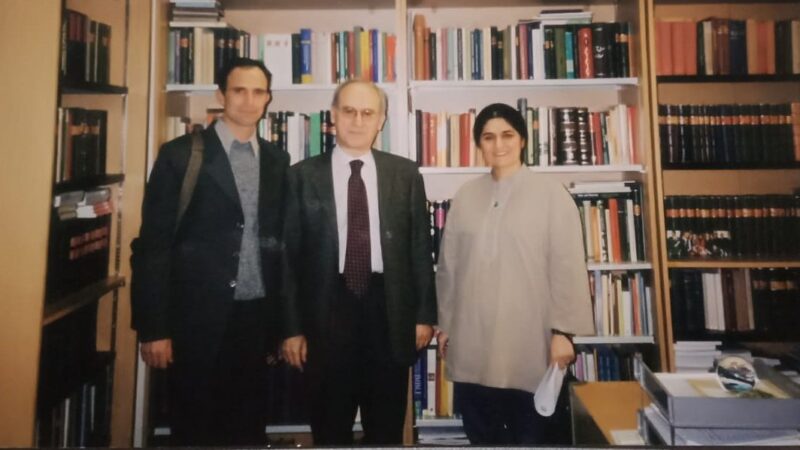

Driven by a commitment to excellence, Dr Angaiz pursued a B.Ed. in 1994, followed by an MA in Organisation, Planning and Management in Education from the University of Reading, UK, and an EdD (Doctor of Education) from Dowling College, Long Island, New York. She continued to serve in AKES institutions in Sher Qila and Gahkuch before eventually transitioning to higher education, heading the education department at Karakoram International University, the first and only university in Gilgit-Baltistan.

Education as Legacy

On International Education Day, stories such as those of Gul Fatima and Dr Dil-Angaiz remind us that education is never an individual achievement alone. It is built on intergenerational sacrifice, institutional vision, and quiet acts of courage, often by women whose courage and labour usually remain unrecorded in formal histories. Their journey illustrates how access to education can reconfigure not only personal destinies but entire regions.

The IIS OHP plays a crucial role in documenting such narratives, preserving voices, memories, and lived experiences that might otherwise fade from collective memory. By recording stories like these, the OHP ensures that future generations can understand how education in places like Gilgit-Baltistan was not simply received but arduously earned, defended, and sustained. In doing so, it safeguards a legacy that continues to inspire new struggles, new aspirations, and new meanings of education in changing times.

About the author

Kiran Rahim is a researcher and development practitioner with expertise in social inclusion, justice and fundamental rights and freedoms in Pakistan. She holds a BS in Politics and International Relations (IIUI, Pakistan), an LLM in Human Rights (University of Edinburgh) and is a GPISH alumna (cohort 2017). She is currently based in Islamabad, Pakistan.