Abstract

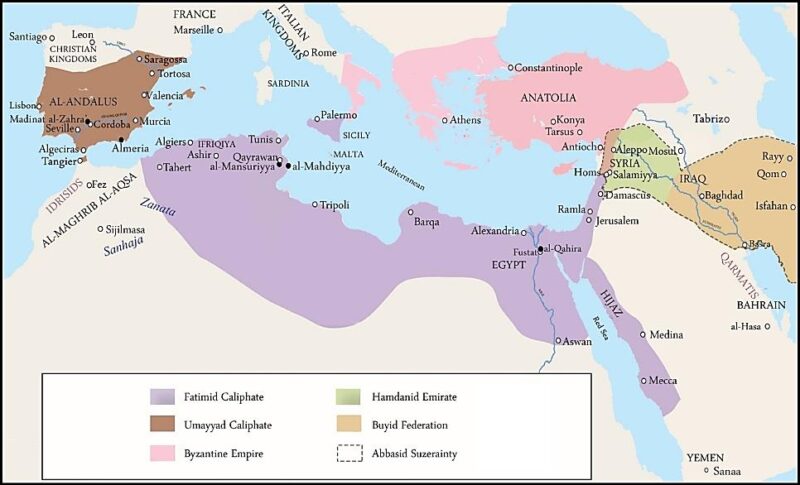

Nizārī Ismailis belong to a branch of Shiʿi Islam who believe in the continuity of the succession to the Prophet Muhammad through, Ismāʿīl, the second eldest son of Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq (d. 765). The early Ismailis went through several stages of evolution in their beliefs and political achievements, including a period of concealment (satr) (during which the Ismaili Imams operate clandestinely), leading to the establishment of the Fatimid state (in 909). The apogee of the Shiʿi Ismaili Imams’ power was reached during the reign of the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs.

Originally published in Illinois Geographer Vol 65, Spring-Fall 2023, Numbers 1-2. Published online with permission.

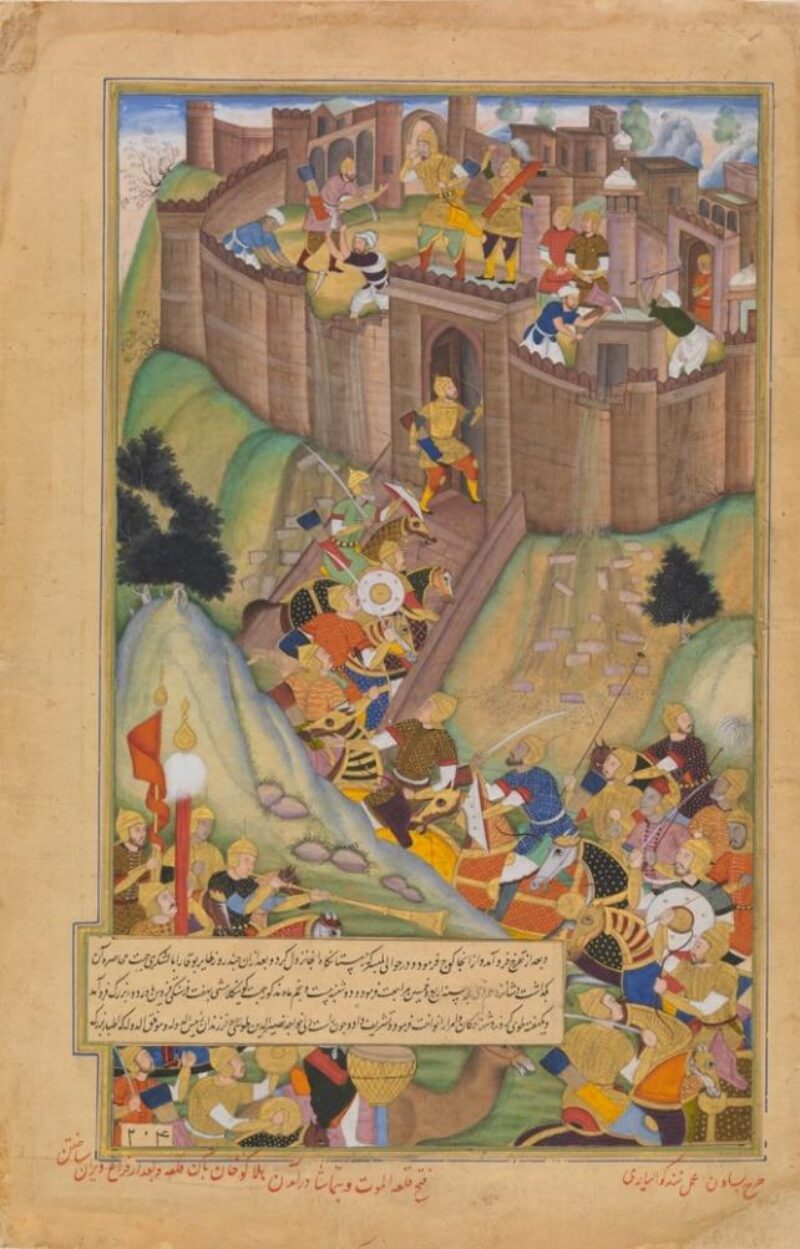

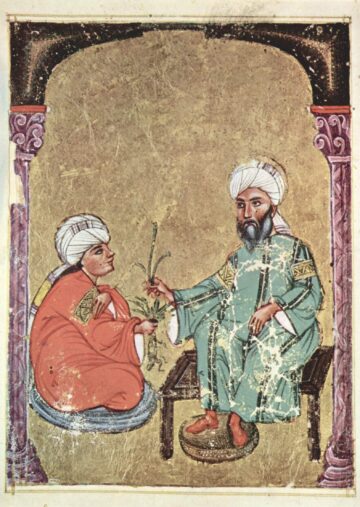

The history of the Nizārī Ismailis practically starts with the dispute over the succession of the eighth Fatimid Imam-Caliph, al-Mustanṣir bi’llāh (d. 1094). At the centre of the dispute is Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ (d. 1124), the senior Persian dāʿī who had arrived in Cairo at the suggestion of ʿAbd al-Malik-i ʿAttāsh, the chief of the Persian Ismaili mission (daʿwa) who owed their allegiance to the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs. A few decades before the demise of al-Mustanṣir, Nāṣir-i Khusraw (d. after 1070), another Persian figure, had arrived in Cairo and was despatched as the most senior chief of the territory of Khurāsān (ḥujjat-i jazīra-yi khurāsān). Nāṣir-i Khusraw was the link that later on connected the Fatimid daʿwa to its Persian followers; he wrote almost entirely in a very Persian with a refined style that remains one of the pillars of Persian poetry and prose. Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ is the continuity of the same tradition which became the centre of one of the most prominent remaining branches of the Ismailis: it is with these people that the Persian language – as opposed to Arabic – becomes the dominant language of the Nizārī Ismailis for many centuries until contemporary times. Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ arrived in Cairo at a time of crisis. The Fatimid state had gone through a famine and the breakdown of law and order. Under these circumstances Badr al-Jamālī (d. 1094), an Armenian general in Syria, helped the Fatimids restore peace and order. Badr al-Jamālī’s son, al-Afḍal, became the powerful vizier of al-Mustanṣir after the death of his father. According to Nizari sources, Nizar, born in 1054, the eldest son of al-Mustanṣir, was designated by his father to succeed him as the next Imam-Caliph. Al-Afḍāl, who favoured the youngest son of al-Mustanṣir, Abu al-Qāsim Aḥmad (al-Mustaʿlī), who was married to his sister. Following the death of al-Mustanṣir, al-Afḍal’s swift action to obtain the allegiance of the Fatimid nobles and the Ismaili daʿwa in Cairo, led to the rise of al-Mustaʿlī to the throne of the Fatimid empire.

Fatimid Ismaili Imam-Caliphs

| al-Mahdi (d. 934) | |

| al-Qaʾim (d. 946) | |

| al-Mansur (d. 953) | |

| al-Muʿizz (d. 975) | |

| al-ʿAziz (d. 996) | |

| al-Hakim (d. 1201) | |

| al-Zahir (d. 1036) | |

| al-Mustansir (d. 1094) | |

| al-Mustaʿli (d. 1101)

↓ Mustaʿlian Imams |

Nizar (d. 1095)

↓ Nizari Imams |

The oral traditions of Nizārīs speak about a son of Nizār taken secretly to Persia to live in the vicinity of Alamūt. This son is the one to whom Ḥasan ʿala dhikrihi’l salam traces his lineage to. The official genealogy of Nizārī Imams mentions three names: al-Hadī, al-Muhtdadī and al-Qāhir.

From the time of Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāh until Ḥasan ʿala dhikrihi’l salam comes forward first as the deputy of the concealed Imam and then as his successor and son, there are a number of key developments in Ismaili thought which are of great importance.

The first one starts with Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ himself who is generally known as a military strategist and political leader, eclipsing his more important role as a chief dāʿī titled ḥujjāt (literally meaning ‘proof’ indicating the highest rank immediately after the Imam). Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ’s major contribution to Ismaili thought can best be summarised in the introduction of the doctrine of taʿlīm (literally meaning ‘instruction’). The doctrine or principle of taʿlīm deals specifically with the subject of knowledge of God which is a critical element in Ismaili thought.

From the early Fatimid period, Ismailis consistently refused to treat the subject of God under prevalent theological categories of other Muslims or typical narratives of philosophers. God beyond being, beyond any attributes, became a category which was central to Neoplatonic Fatimid thought (see Madelung in Nasr, 1977:53-65; see also: Walker, 2008). Until the time of Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ, this principle was primarily referring to the central theme of establishing the legitimacy of the line of succession of Shiʿi Ismaili Imams in terms of leadership among other cosmological considerations in terms of the status of the Imam. The Alamūt period represents a major shift in the sense that the Nizārī cosmology had now woven into the belief in Imamat, elements of tawḥīd, and the perfection of ritual laws by emphasising their inner ethical contents. This emphasis was embodied in the declaration of qiyāmat (resurrection) as a marker of the specific Nizārī identity. The declaration of resurrection meant that for those people who have reached the higher stages of spiritual perfection (ahl-i waḥdat), and not for categorically everyone, adherence to ritual laws was not necessary, even though conditions for reaching that stage were quite strict (see: Ṭūsī, 2010:42-43; and 2005:115; for a detailed discussion of spiritual resurrection, see Shahrastānī, 2021:24-27).

As mentioned earlier, Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ was the founding figure of this shift in thinking and can be compared with the earlier pillars of Ismaili thought like al-Sijistānī, al-Kirmānī and Nāṣir-i Khusraw. He not only represented a political break from the Fatimid empire, but he also introduced a shift from the densely Neoplatonic system of thought to a much more benign and diluted version which was now restructured around a basic idea of knowledge of God through an individual man. It is an error to reduce this new articulation to a mere belief in the authority of the ‘infallible Imam’ – as al-Ghazālī had summarised it in his polemical works against Nizārīs (for a detailed study of al-Ghazālī’s work, see Mitha, 2001). One of the key figures in the formulation and rearticulation of the principle of Imamat for Nizārī Ismailis is Muḥammad al-Shahrastānī whose impact and massive influence on all later Nizārī works is now very well established. Al-Shahrastānī lived during the later years of the life of Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ until the early years of the life of Ḥasan ʿala dhikrihi’l salam. Among his works, there are at least three which contribute significantly to this shift: 1. His magnum opus, the al-Milal wa al-niḥal, which is the earliest source that offers a summarised Arabic version of Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ’s Chahār faṣl on taʿlīm; 2. His Mafātīḥ al-asrār wa maṣābīḥ al-abrār which contains the key elements and methodology of the esoteric exegesis vastly used by Nizārī Ismailis; and 3. The Majlis-i maktūb (now published under the title of Command and Creation; for a detailed discussion of these books, see Shahrastānī, 2021) which is delivered in Persian.

The continuum of Ismaili thought from the time of Ḥasan-i Ṣabbāḥ until the final years of the Alamut state with the contributions of Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī crystalises a very distinct identity for Nizārī Ismailis from their sister Ismaili communities. The works attributed to al-Ṭūsī played a significant part in shaping the Nizari Ismaili thought and also articulating in further depth principles of tawḥīd, imāmat, qiyāmat and taʿlīm, which were central to Nizari Ismaili thought. The most prominent works of al-Ṭūsī on Nizari Ismaili thought are: 1. Rawḍa-yi taslīm; 2. Sayr wa suluk; 3. Āghāz wa anjām; 4. Maṭlūb al-muʾminīn; 5. Akhlāq-i Muḥtashamī; and 6. Tawallā wa tabarrā. Except for the Akhlāq-i Muḥtashamī, all these works are edited, translated into English and published by the Institute of Ismaili Studies.

dāʿīs and ḥujjas

| Hasan-i Sabbah (1090-1124) |

| Kiya Buzurg-Umid (1124-1138) |

| Muhammad b. Buzurg-Umid (1138-1162) |

Imams

| Ḥasan ʿala dhikrihi’l salam (1162-1166) |

| Nur al-Din Muhamad (1166-1210) |

| Jalal al-Din Hasan (1210-1221) |

| ʿAla al-Din Muhammad (122101255) |

| Rukn al-Din Khurshah (1255-1256) |

Nizārī esotericism had now moved closer to a version of Sufism that contained both rational elements and an emphasis on allegorical interpretations of faith. They had also slowly moved away from the densely philosophical Neoplatonism of earlier periods (see Mohammad Poor, in Mir-Kasimov, 2020: 219-245).

With the collapse of the Alamut state at the hand of the Mongols, another period of concealment began which lasted until a period which is known as the Anjudān revival period. After Rukn al-Dīn Khurshāh (d. 1257), the 27th Nizārī Ismaili Imam, the oral traditions of the community mention four Imams who lived in concealment following the tragic massacre of Ismailis and the destruction of their intellectual heritage. The names are Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad, Qāsim Shah, Islām Shah and Muḥammad b. Islam Shah. This concealment period also witnessed another schism among Nizārī Ismailis over the succession of Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad (see Daftary, 2020). Those who adhered to the succession of Qāsim Shah are now the Ismailis who acknowledge the authority of their 49th Imam, Karim Aga Khan IV. Therefore, the precise name of this branch can be recorded as Nizārī Qāsim Shahī Shiʿi Ismaili Muslims. The other branch of Nizārīs is the Muḥammad Shahī branch. The most prominent figure of this line of Imamat was Shah Tahir al-Husayni (d. 1594) who propagated a form of Ismailism under the guise of Twelver Shiʿism. The line of the Muḥammad Shahī Imams discontinued in the final decades of the 18th century and the the Muhammad Shahī Ismailis either merged with the Qāsim Shahī line or assimilated into Twelver Shiʿism (Daftary, 2011:405).

From the time of Mustanṣir bi’llah II (d. 1480) who was the first Imam of the Anjudan revival period, Nizārī Ismailis slowly emerged from concealment cautiously asserting more visible roles in society. By this time, Twelver Shiʿism had become the official state religion in Iran under the Safavids. Nizārī Ismailis had also started a closer relationship with various Sufi groups including the Niʿmatullāhī order. This stage of Nizārī Ismailism lasts for about four centuries until the departure of the 46th Ismaili Imam, Aga Khan I, to India (in 1840). During this period, Ismaili thought closely intermingled with both Sufism and Twelver Shiʿism to the extent that until the time of the 48th Ismaili Imam, Aga Khan III (d. 1957), it would be difficult to distinguish Ismaili identity from that of Sufis or Twelvers.

By the time of the first Aga Khan (d. 1881), the Nizārī Ismailis who accepted this line of Imamat were spread in Iran, Syria, Central Asia, China and India with some early communities who had moved to East Africa, with Zanzibar being an important entry point for Nizārī Ismailis of the Indian Subcontinent known as the Khojas (see Hirji, Zulfikar, in Daftary, 2011:129-159). In his memoirs, the Aga Khan refers to ‘India, Khurāsan, Turkistān and Badakhshān’ as centres where Ismailis had sent aid to their Imam during the process of his fleeing Persia (see, The First Aga Khan, p. 93). Settlements of Nizārī Ismailis from the subcontinent are reported to have started during the time of the 45th Ismaili Imam, Shah Khalil Allah (d. 1817). The devastating Mongol invasion, their massacre of Ismailis and the destruction of their intellectual and literary heritage did not uproot Nizārī Ismailis. They were scattered all around the globe while always maintaining close contacts with their Imams and the continued line of succession. The movement of Ismailis to East Africa during the Imamat of the first three Aga Khans was accompanied by major changes and developments in the social structure of the community and a shift in the way Ismaili Imamat exercises its authority over the vastly diverse community it had. The Uganda crisis during the rule of Idi Amin led to a migration of Ismailis to Europe and North America in larger numbers mainly among the Nizārī Ismailis from the subcontinent. Ismailis from Northern Areas of Pakistan, China, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Iran and Syria had linguistic and cultural differences with Ismailis from the subcontinent while sharing their allegiance to the line of Nizārī Qāsim Shahī Imams.

References

Aga Khan I. The First Aga Khan: Memoirs of the 46th Ismaili Imam. Edited by Daniel J. Beben and Daryoush Mohammad Poor, I.B. Tauris in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2018.

Aga Khan IV, and Adrienne Clarkson. Where Hope Takes Root: Democracy and Pluralism in an Interdependent World. Douglas & McIntyre, 2008.

Daftary, Farhad. The Ismaili Imams: A Biographical History. The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2020

Daftary, Farhad. A Modern History of the Ismailis: Continuity and Change in a Muslim Community. I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Daftary, Farhad. The Assassin Legends Myths of the Ismaʿilis. Reprint, I. B. Tauris, 2001

Daftary, Farhad. The Ismāʿīlīs: Their History and Doctrines. 2nd ed, reprinted with corrections, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Kersten, Carool. Contemporary Thought in the Muslim World: Trends, Themes and Issues. Routledge, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2019.

Mir-Kasimov, Orkhan (ed.). Intellectual Interactions in the Islamic World: The Ismaili Thread. I.B. Tauris, 2020.

Mitha, Farouk. Al-Ghazālī and the Ismailis: A Debate on Reason and Authority in Medieval Islam. I.B. Tauris, 2001.

Mohammad Poor, Daryoush. Authority without Territory: The Aga Khan Development Network and the Ismaili Imamate. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. Ismāʿīlī Contributions to Islamic Culture. Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy, 1977

Sedgwick, Mark. Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. [Print on demand ], Oxford University Press, 2011.

Shahrastānī, Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Karīm. Command and Creation a Shi’i Cosmological Treatise: A Persian Edition and English Translation of Muhammad Al-Shahrastani’s Majlis-i Maktub. Edited by Daryoush Mohammad Poor, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2021.

Ṭūsī, Naṣīr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad, et al. Paradise of Submission: A Medieval Treatise on Ismaili Thought. I.B. Tauris in association with Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2005.

Ṭūsī, Naṣīr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad, et al. Contemplation and Action: The Spiritual Autobiography of a Muslim Scholar. New ed, I.B. Tauris, 1998.

Ṭūsī, Naṣīr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad, et al. Shi’i Interpretations of Islam: Three Treatises on Theology and Eschatology. I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Walker, Paul Ernest. Early Philosophical Shiism: The Ismaili Neoplatonism of Abu Yaʼqub Al-Sijistani. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

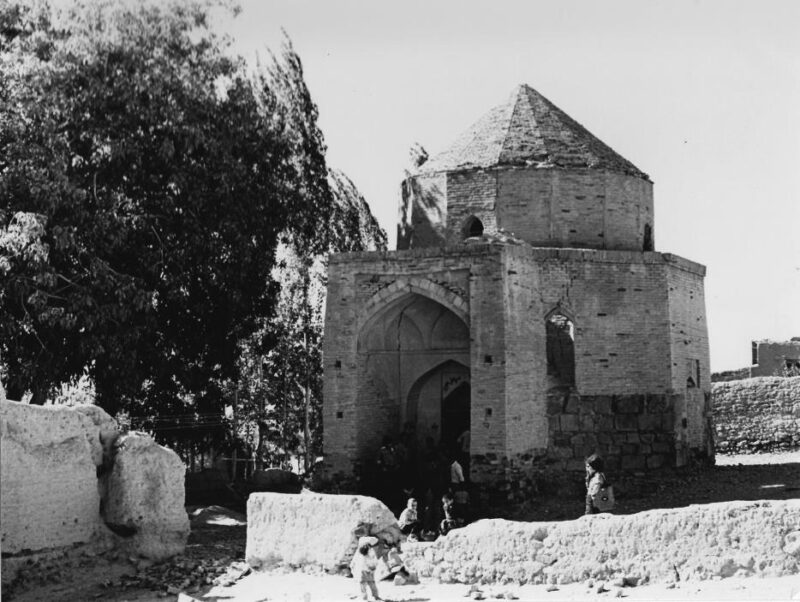

Willey, Peter, and Institute of Ismaili Studies Staff. Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. I.B. Tauris, 2014.

Author

Dr Daryoush Mohammad Poor

Dr Daryoush Mohammad Poor is the Interim Head of the Constituency Studies Unit, Associate Professor in the Department of Academic Research and Publications at The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, and a lecturer for the Department of Graduate Studies. He is also the editor of the Ismaili Heritage Series.