Women Who Have Impacted Ismaili History

Throughout its long history, the Ismaili Muslim community has encountered moments of triumph and glory as well as times in which the safety and security of the community was in danger.

In the Fatimid period (909-1171 C.E.), the Ismaili Imams founded cities as Caliphs of an empire spanning the Mediterranean, and left an indelible mark on the intellectual, cultural, social and religious fabric of Muslim history and world civilisation. Through the building of social governance structures, institutions of learning and wonderful architecture, ceremonial pageantry and commemoration of festivals, the Ismaili Imams stamped their mark on the Muslim, and greater world, history. In more troubling times, the community and their Imams also suffered brutal persecution. In these moments the Imams and the community needed to live under different guises, retreating at various junctures into villages and remote mountain fortresses to safeguard their very lives.

In charting the history of the Ismailis, one will recognise that its survival, as well as its flourishing in the modern period of world history, has rested upon the dynamic leadership of its Imams and the strength and courage of special individuals. Many times, we see and hear these voices from the lips of men. In this brief article, we will turn instead to some of the wise, powerful and influential women who shaped Ismaili history. It is these women whom we honour during this Women’s History Month.

Sitt al-Mulk (d. 1023 C.E.)

During the reign of the Fatimid Imam-Caliph, al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah (d. 975 C.E.), the Fatimid palace witnessed the birth of a baby girl, a young princess, daughter to the next Fatimid Imam-caliph al-Aziz bi’llah and his wife al-Sayyida. Born in 970 C.E., the young girl was given the title, Sitt al-Mulk, ‘Lady of the Empire’, and “was presented by the chronicles as the apple of her father’s eye, but even so, few could have then imagined the pivotal role she would play in the decades that followed.”1

Sitt al-Mulk became a renowned entrepreneur of her time. She also wielded considerable political influence at the Fatimid court. At a time when these pursuits were considered to be the forte of men, the presentation of Sitt al-Mulk’s life and legacy in the sources must be understood in that light. As well, they need to take into consideration the religious, political and economic climate during the reign of her half-brother, the Fatimid Imam-Caliph, Hakim bi Amr Allah (d. 1021 C.E.). As has been stated, “The full extent of Sitt al-Mulk’s rise to power ought to be measured against the background of the shifting balance of power amongst the fiercely rival factions who aimed to retain control of the court, along with its administrative and political institutions.” 2

Sitt al-Mulk’s significant role extended to ensuring continuity of leadership during the vital moment of transition in leadership. On the death of Imam-Caliph al-Hakim, she was instrumental in securing the succession of her nephew, the Imam-Caliph al-Zahir, and acted as his regent, the de facto ruler of the state for the first few years of his rule until her death on 5 February 1023 C.E.

Queen Arwa al-Sayyida al-Hurra (d. 1138 C.E.)

During the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mustansir bi’llah’s (d. 1094 C.E.) 58-year rule, a powerful woman rose through the ranks to wield significant influence in the corridors of Fatimid power. Sayyida Arwa bint Ahmad al-Sulayhi, also known as al-Sayyida al-Hurra, the Noble Lady, and al-Malika, the Queen of Yemen, was a significant figure in Ismaili history, having positions of power till her death in 1138 C.E. Additionally, her influence came once again to the fore in the immediate aftermath of the Imam al-Mustansir’s death and ensuing crisis of succession amongst his sons.

History records that the Sulayhid dynasty emerged in Yemen during the Fatimid period. Prior to the inception of Fatimid rule in 909 C.E., its missionary activity, the da‘wat al-hadiya, rightly-guiding summons, had established a stronghold in Yemen. Under the Imam-Caliph al-Mustansir, leadership was vested in the da‘i Ali bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi (d. 1067 C.E.), a chieftain of the influential Banu Hamdan, after whom the dynasty took its name. On his death, his son Ahmad al-Mukarram (d. 1084 C.E.) succeeded him. It was in the latter years of Ahmad’s reign when he fell ill, that his wife, Sayyida Arwa effectively held the reins of power.

The esteem in which she was held can be seen in her appointment by the Imam as the hujja of Yemen, a rank which, in the Fatimid hierarchy of religious leadership, was second only to that of the Imam himself. Al-Mustansir also “charged her with the affairs of the da‘wa in western India… around 460/1067, Yamani daʿis were despatched to Gujarat under the close supervision of the Sulayhids. These daʿis founded a new Ismaili community in Gujarat which in time grew into the present Tayyibi Bohra community.”3

On the death of al-Mustansir however, conflicting historical accounts can be found surrounding the events that followed. The literary heritage of the communities who would come to follow two different sons of the Imam present differing narratives. The followers of Nizar b. al-Mustansir (d. 1095 C.E.), today known as the Nizari Ismailis, followers of His Highness the Aga Khan as the 49th hereditary Imam in direct descent from the Prophet, upheld Nizar’s rights to succession as the originally designated heir who had been nominated by his father by way of nass, explicit designation. According to the Nizaris therefore, his designation as the next Ismaili Imam-Caliph was final “with the irrevocability of the nass a central tenet of Shiʿi Ismaili doctrine.”4

On the other hand, those who accepted the claims of Nizar’s younger half-brother, Abu’l-Qasim Ahmad to the Fatimid throne, became known as the Musta‘alis, after his regnal title al-Mustaʿli bi’llah (the one Elevated by God)5. “The Musta‘lian Ismailis split into [two] branches on the assassination of al-Musta‘li’s son and successor al-Amir in 1130.”6 At this point, “the Musta‘lian community of Sulayhid Yemen recognised the imamate of al-Amir’s infant son al-Tayyib and became known as the Tayyibiyya.”7 It was to this lineage of Imam-Caliphs that Sayyida Arwa bint Sulayhi, pledged her allegiance and support.

Bibi Sarkara Maryam Khatoon (d. c. 1832 C.E.)

In the modern period of Nizari Ismaili history, sometimes known as the period of the “Aga Khans”, we see the power and influence of women once more, this time in the figure of one Bibi Sarkara Maryam Khatoon, also known as ‘Mata Salamat’, the title, meaning ‘Mother of Peace’. She was the wife of the 45th Ismaili Imam, Shah Khalil Allah (d. 1817 C.E.) and mother of the 46th Imam, Hasan Ali Shah, Aga Khan I (d. 1881 C.E.).

Since the split of the Fatimids into the Tayyibis, who took control of the line of Imam-Caliphs in Egypt in 1094 C.E. and the Nizari Ismaili Imams and their followers, who also claimed that legacy, the latter sought refuge in the fortress of Alamut and other mountain fortresses in Iran. For close to 700 years – at times under taqiyya (precautionary dissimulation) and at others, more openly forging relations with the rulers of Persia – 26 of the 49 Ismaili Imams resided in Persia. In approaching the end of the 18th century, a shift was underway. In 1817 C.E., the 45th Imam, Shah Khalil Allah “lost his life [when] a mob attacked the imam’s house. In the ensuing uproar, Shah Khalil Allah and several of his followers… were murdered, and the imam’s house was plundered.”8

At this critical juncture, it was Mata Salamat, the wife of the murdered Imam and mother of the 46th Imam, Hasan Ali Shah, then aged 13 years, who confidently went to the court of the ruling Qajar dynasty in Tehran, to seek justice for her husband and son. It was as a result of her petition that the Qajar monarch, Fath Ali Shah, brought the Imam’s killers to justice. In addition to this, Mata Salamat secured land holdings for her son in Mahallat to ensure that the family was provided for and that the young Imam’s rights were preserved. The monarch also offered his daughter, Sarv-i Jahan Khanum’s hand in marriage to the 46th Imam. It was at this point also that the title of “Aga Khan”, meaning ‘Lord’ and ‘Master’ was bestowed upon the young Imam. To this day, the title has remained hereditary amongst the descendants of Imam Hasan Ali Shah. The Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 2017 of the 49th Ismaili Imam, Shah Karim al-Husayni, His Highness the Aga Khan IV (b. 1936 C.E.) also marked 200 years since the title Aga Khan had been bestowed on the 46th Imam in 1817.

During the 64-year-long Imamat of her son, Imam Hasan Ali Shah, he bestowed upon her the esteemed title of Pir and sent her to India to settle disputes within the community. It is recorded that she also delivered many sermons in the Jamat, facilitating its religious formation and development. Pir Mata Salamat thus embodied, like many women in the Ismaili Muslim Jamat today, the principles of strong female leadership, both in the community’s social as well as spiritual and religious growth and upliftment. She died in Kutch, India in 1851.

Sayyida Imam Begum (d. c. 1866 C.E.)

During the time of the 46th Nizari Ismaili Imam, Hasan Ali Shah, Aga Khan I (d. 1881 C.E.), there emerged a literary composer of devotional poems in the South Asian Ismaili community, known as Sayyida Imam Begum, who is recognised as one of the most well-known female composers of a genre of spiritual and devotional poems known as ginans.

Historiographical traditions within the Ismaili community attribute the composition of these ginans to a series of Nizari Ismaili daʿis, missionary-preachers, known as Pirs and Sayyids, who are believed to have been designated by the Ismaili Imams from as early as the 11th and 12th centuries with the mission of propagating the teachings of “Satpanth” or “True Path” in the Indian Subcontinent. Through their devotional compositions, the Pirs and Sayyids sought to highlight the significance of accepting the authority of the living Ismaili Imam.

As explained by various authors, the ginans are “powerful in imagery and symbolism drawn from the cultural milieu of the Indian Subcontinent.”9 Rooted in multiple movements and discourses within the Subcontinent at the time, the ginans encompassed a wide variety of themes, many of which can be found in the compositions of Sayyida Imam Begum who was “the last of the ginan composers and the only female figure in the Tradition.”10 History records that she spent most of her life in or near Bombay, was an accomplished player of sarangi (the fiddle) and “used to compose and sing ginans to the jama‘at as part of her duties to propagate the da‘wa.”11

According to one scholar, Sayyida Imam Begum composed a “small number of Ginans of great beauty, especially notable for their imploring tenderness and meditative intimacy.”12 Focusing on these themes of love, devotion and a desirous yearning for union with the beloved, Sayyida Imam Begum’s ginans continue to be recited today throughout South Asian Nizari Ismaili communities today. She passed away in Karachi sometime around 1866 C.E.

Endnotes

- Jiwa, S. The Fatimids 2: Rule from Egypt (I.B. Tauris in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2023), p. 58.

- Cortese, D. and Calderini, S. Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam (Edinburgh University Press, 2006), p. 117.

- Daftary, F. Ismaili in Medieval Muslim Societies (I.B. Tauris in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2005), p. 80.

- Jiwa, S. The Fatimids 2: Rule from Egypt (I.B. Tauris in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2023), p. 155.

- Jiwa, S. The Fatimids 2: Rule from Egypt (I.B. Tauris in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2023), p. 154.

- Daftary, F. Ismaili History and Intellectual Traditions (Routledge, 2018), p. 29

- Daftary, F. Ismaili History and Intellectual Traditions (Routledge, 2018), p. 30

- Daftary, F. The Ismailis. Their History and Doctrines. Second Edition (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 463.

- Gillani, K. “The Ismaili "Ginan" Tradition from the Indian Subcontinent” Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, Vol. 38, No. 2 (2004): 175-176.

- Nanji, A. The Nizari Ismaili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent (Caravan Books, 1978), p. 94.

- Nanji, A. The Nizari Ismaili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent (Caravan Books, 1978), p. 94.

- Esmail, A. A Scent of Sandalwood. Indo-Ismaili Religious Lyrics (Ginans) (Curzon Press, 2002), p. 13.

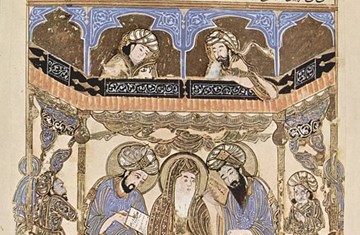

Image: an illustration from Maqāmāt al-Ḥarīrī. Public domain.

Pabani, Nadim. "Women Who Have Impacted Ismaili History" Lifelong Learning, The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 13 March 2024, https://www.iis.ac.uk/learning-centre/scholarly-contributions/lifelong-learning-articles/women-in-ismaili-history/

Pabani, Nadim. (2024, March 13) Women Who Have Impacted Ismaili History. Lifelong Learning. https://www.iis.ac.uk/learning-centre/scholarly-contributions/lifelong-learning-articles/women-in-ismaili-history/

Pabani, Nadim. "Women Who Have Impacted Ismaili History" Lifelong Learning (blog), The Institute of Ismaili Studies, March 13, 2024. https://www.iis.ac.uk/learning-centre/scholarly-contributions/lifelong-learning-articles/women-in-ismaili-history/.

Pabani, Nadim. 2024. "Women Who Have Impacted Ismaili History" Lifelong Learning (blog), The Institute of Ismaili Studies, March 13. https://www.iis.ac.uk/learning-centre/scholarly-contributions/lifelong-learning-articles/women-in-ismaili-history/.