Azim Nanji, Director of The Institute of Ismaili Studies, began the formal proceedings by situating the development and progress of the Institute within the larger Ismaili commitment to education. As early as the tenth century, the Fatimid imam al-Mu‘izz established al-Azhar university in Cairo and the library at Alamut was a repository of knowledge for the Ismaili communities of 12th and 13th century Iran.

Over the years, the Institute has built a reputation that attracts high-calibre students from around the globe. This year’s graduating class included students from seven countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and North America. As early as 1980, the Institute had initiated several programmes in collaboration with universities in Canada and the United Kingdom in which students obtained Masters degrees in Education and Islamic Studies. Since 1994, the Institute has offered a Graduate Programme in Islamic Studies and Humanities in which students from various academic backgrounds have converged in London for a two-year course after which they have read for their Masters at a British University in a field of their interest.

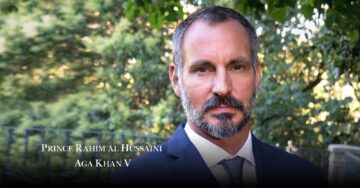

The Aga KhanA title granted by the Shah of Persia to the then Ismaili Imam in 1818 and inherited by each of his successors to the Imamate., spiritual leader (imamIn general usage, a leader of prayers or religious leader. The Shi’i restrict the term to their spiritual leaders descended from ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima.) of the Ismaili community and Chairman of the Institute’s Board of Governors, in his opening address, described the intellectual development of the umma as an urgent challenge. “In what voice or voices,” he asked, “can the Islamic heritage speak to us afresh — a voice true to the historical experience of the Muslim world yet, at the same time, relevant to the technically advanced but morally turbulent and uncertain world of today?”

Presenting what he acknowledged was a grey picture of the umma, the Aga Khan said “unless we have the courage to face unpleasant reality, there is no way that we can aspire realistically to a better future.”

He spoke of divides so readily perceived today.

“On the opposite sides of the fissures are the ultra-rich and the ultra-poor, the Shi‘a and the Sunni, the Arab and the non-Arab, the theocracies and the secular states, the search for normatisation versus the valuing of pluralism, those who search for and are keen to adopt modern, participatory, forms of government versus those who wish to re-impose supposedly ancient forms of governance. What should have been brotherhood has become rivalry, generosity has been replaced by greed and ambition, the right to think is held to be the enemy of real faith, and anything we might hope to do to expand the frontiers of human knowledge through research is doomed to failure for, in most of the Muslim world, there are neither the structures nor the resources to develop meaningful intellectual leadership.”

“Yet,” said the Aga Khan, “there are many across the length and breadth of the Muslim world today, who care for their history and heritage, who are keenly sensitive to the radically altered conditions of the modern world… They are convinced,” he said, “that the idea that there is some inherent, permanent division between their heritage and the world of today is a profoundly mistaken idea; and that the choice it suggests between an Islamic identity on one hand, and on the other hand, full participation in the global order of today is a false choice indeed.” The Aga Khan went on to describe a number of initiatives that he had launched in the areas of higher education to address the need to foster intellectual development in Muslim societies. These included the Aga Khan University with campuses in South Asia, East Africa and the United Kingdom and the University of Central Asia with campuses under development in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic.

Concluding the formal ceremonies, Class of 2004 valedictorian, Sabrina Datoo from Canada, spoke about the challenges and realities of managing plurality in the current global landscape. Reflecting on her experiences over the last two years at the IIS, Sabrina spoke about some of the challenging encounters between her and her fellow classmates. “Our classroom discussions were often tense: differing ideologies, differing visions of ‘the good life’ emerged in competition. Yet in retrospect, our classes were fascinating because of this very fact,” commented Sabrina. “We clamoured to contribute our personal experiences and defend our points of view. Those passionate discussions were part of a process of coping with our differences.”

Sabrina also encouraged the Institute to continue to invest in facilitating a social environment where students could build friendships. She argued that, “ties of co-operation, may likely build the foundation of the tolerant, cosmopolitan, global community that we envisage for the future.”